"God, I Have Some Questions": Re-reading Genesis 3 with Danbala and Ayida on Saint Patrick’s Day

Originally published on Lanbi ak Manchèt.

by Nyya Toussaint

Lessons Christians can learn from Haitian Vodou in their theological questioning

Today (3/17/2023) the Catholic Church and Irish communities celebrate the feast day of Saint Patrick: the patron saint of Ireland who has been informally canonized for evangelizing to the Irish people and, according to legend, getting rid of all of their isle’s snakes. Although research proves it is improbable that snakes ever existed in Ireland, Saint Patrick’s epic highlights Christianity’s continued outlook on serpents as demonic and lethal tempters.

"Ayida" by Fermina Esoterica

As a young child, I spent much time on my paternal family's land in Alligator, North Carolina. I learned how to clean and cook greens, remember my ancestors, and “love one another” on our 18 acres of land. I will never forget being a suburban boy encountering snakes in the deep country. Our family cemetery always had signs of snakes living among our ancestors. One day after visiting the graveyard, my Poppop intentionally ran over a snake crossing the road with the huge tire of his Yukon. He told my cousins and me, “that was a venomous snake and our family lives here”. Then there was a time when a snake crossed me in the yard. I was sent outside to get an orange-black patterned extension cord laying in the thick, soggy Carolina grass, and as I reached down to grasp it - it began to move! For a moment the entire extension cord had become an orange and black snake, the regular-old cord and the blood-curdling snake were completely inseparable in my eyes. I ran into the house to tell of my encounter and my 70-year-old, Pentecostal-preaching, great-grandmother, Pastor Virginia Andrews, asked “where is the extension cord and where is the snake?” The two were no longer one.

As I led her to the extension cord, to my surprise we encountered the snake still in the yard but away from the extension cord. In mud-stained white rain-boots and a flowy ankle-length skirt, Grandma Gin killed the snake with a gardening hoe and crushed its head into the land she owned with her heel. Remembering her son-in-law riding over that snake years prior, it went unsaid that she was protecting her family but as my Pastor-Grandma she said to me “do not forget the Bible tells us God put enmity between the serpent and the woman, and between the serpent’s seed and her seed; her seed shall bruise the serpent’s head, and the serpent shall bruise our heel.” I walked in awe and silence to pick up the extension cord. Though the extension cord and snake were no longer one, this moment with my great-grandmother was a blow to the male-female, young-old, and spirit-mundane binaries that informed my rearing under U.S. empire.

As a Haitian American and Black American with Pentecostal and Vodou roots, the snake is both as mundane as any other reptile and as spiritual as the very serpent hanging around the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Yet in holding myself accountable for the destruction of the earth and the ways Christianity has played a role in the current climate crisis, I find myself thinking things over about the Serpent from Eden and the ways it informs the inseverable connection between spirituality and the earth and her snakes.

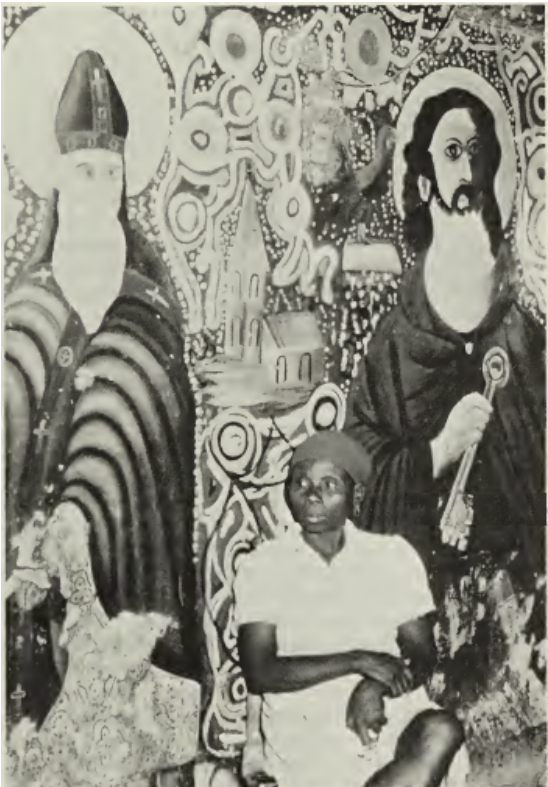

Temple wall painting of Saint Patrick (Danbala) and Saint Peter (Legba). Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1980. Photograph by Judith Gleason.

Enslaved people in Haiti, under the oppression of forced religion and labor, believed the beloved spirit of Da from Dahomey (Benin) could be connected to the snake-slaying Saint Patrick that enslavers obliged on them. In Haitian Vodou, March 17th is the feast of the married couple Danbala Wedo and Ayida Wedo whose names carry “Da”:

“Da is a spirit—or vodu̧ as the Dahomeans say—that represents what might be called life force or, perhaps more accurately, the coiling, sinuous movement that is life's movement…All snakes are called Da, but all snakes are not respected. The vodu̧ Da is more than a snake. It is a living quality expressed in all things that are flexible, sinuous, and moist; all things that fold and refold and coil, and do not move on feet, though sometimes those things that are Da go through the air. The rainbow has these qualities, and smoke, and so have the umbilical cord, and some say the nerves, too.” (McCarthy Brown)

For sèvitè in the Haitian Vodou tradition, Danbala and Ayida represent some of the oldest ancestors Vodou practitioners can call on by name. These lwa’s connections to land, water, and air speak to the lived experience of Haitians and all Black folks in the Americas who slither through the continued perils of living on either side of the Atlantic; who mysteriously carry the creative energy to form rainbows; who seem to always escape the arson committed against them by riding out with the smoke. There is room for exploration of the Haitian serpents' connections to Eden’s serpent when recalling Danbala and Ayida’s reflections within other spiritual symbols like the Mapou tree. Haiti’s giant Mapou trees are the potomitan or potoDanbala (pantheons) for sèvitè to connect with lwa like Ayida and Danbala. The Mapou is also the site where enslaved people spiritually wrestled and questioned their oppression at Bwa Kayiman. Haiti’s' rebellion and revolution reveal that, alongside serpents, if we come with pure intentions it is possible to eat from the holiest trees and survive.

“Dysmorphic Dance II” by Patrick Dougher

Science makes it easy to let go of any reality in Saint Patrick’s legendary tale of becoming the snake slayer; contrarily, it is more complicated in our world to let go of a particular reading of an origin myth that infers a serpent tempted a woman who tempted a man. In our re-reading, we must hold to memory that the text does not say the serpent told Eve to eat from the tree and Eve never needed to seduce Adam into anything. Empire allows us to believe in science but does not allow for a widespread agreement that the most common Biblical interpretations have been used to justify the demolition of the earth, the deeming of women as the inferior temptress, and the continuation of the homoerotic-yet-homophobic clusterf*ck called patriarchy that lets men get away with everything. Yet, on a grassroots level within this empire, we have an opportunity to let go of Christianity’s continued demonization of Eden’s serpent by looking to the most demonized faith tradition in modern times.

Drapo Danbala (Damballa Vodou Banner) by Maxon Scylla

Today our oldest known ancestors, Danbala Wedo and Ayida Wedo, slither in willing to talk with us about those theological questions we have told ourselves were too big for God. To slither, is to find space between the hard rock of immutable religious concepts, to softly seek after and inquire about God’s mysteries that remain unanswered:

“But God, why?”

“Wait, what God?”

“How God, how?”

“Nah God, WHO?!”

“Where are you, God?”

“God, whenever you’re ready…”

In connecting “the past and present and [turning] both into a future that is and is not different from the past”, Danbala and Ayida place our questions for God in a long history of oppressed folks’ confusion, hardship, and ‘waiting on the LORD’. They are the serpents who give up their skin ‘in order to recreate [themselves] and thus remain what it is” (McCarthy Brown). Ayida and Danbala call followers of Jesus to question the intentions of their serpent-cousin from Eden. How was the serpent in Eden so attuned to God’s vision? How long had that serpent been around to not only hear what God told Adam and Eve but also to know that God was exaggerating about a tree being lethal (Compare Genesis 2:17 and 3:22-24)? Like Moses the Liberator, why does this serpent hang in places deemed by God as too holy for humanity (See Exodus 19:12, Exodus 33:7-11, Leviticus 16:17)? Can we trust ourselves to explore the mysteries of God, like a snake in the garden, without losing our faith in the wilderness?

This Fèt Danbala ak Ayida, Feast of Saint Patrick, and mundane Friday, March 17, 2023, can we let go of the stories we tell ourselves about the serpent to experience the mystery of peace amidst questioning and to stop crushing our heals into the snake's head?

I pray for your peace today. I pray for the mysteries you have yet to solve. I pray for your commitment to creative excellence even though you do not know it all nor can you do it all. May there be rainbows in the skies where there is drought- that you do not have to support the sun on your back anymore (m pa ka sipòte solèy sou do mwen), that you may traverse lands and cross waters, that you may have pure intentions and a cool head (tèt fret) before your God.

References:

Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn Updated and Expanded Edition by Karen McCarthy Brown, 2001

Nyya Toussaint

Nyya Toussaint is a Haitian American and Black American scholar of the Sociology of Religion, Black Linguistics, and International Affairs. He attended Florida International University where he majored in Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Sociology, and International Affairs. Nyya holds certificates in Haitian Studies and Latin American and Caribbean Studies from the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center and participated in the center's study abroad in Buenos Aires. As a FLAS Fellow, Nyya forged and led FlU's long-term partnership with Duolingo and the Konbit Kreyol Ayisyen, resulting in 403K online learners of Haitian Creole. Nyya is the first dual-degree graduate between Union Theological Seminary and The New School where he, respectively, attained a MA in the sociology of Religion and MA in International Affairs. Hundreds of people have gathered for Nyya's public programs on Caribbean cultures and spiritualities and his recorded events garner thousands of playbacks. He has presented his academic research on linguistics, international affairs, and Black spirituality and social movement globally. He is the Founding Creative Director of Lanbi ak Manchèt; a cultural and spiritual organizing hub. Nyya is a board member of KOSANBA, a Year 5 Fellow of the Intercultural Leadership Institute, executive member of the Haitian Studies Association, and member of the Political Theology Network. Nyya is a candidate for ordination as a non-denominational pastor.